by Cynthia Costain

Carol sat on her bed and looked at her big cabin trunk. It was all packed and ready to be loaded onto the ship tomorrow morning when she, Dad, and Doris would set sail for England. Her clothes were lying on the top of the trunk; white cotton camisole, drawers and petticoat, navy blue skirt and sailor blouse, black stockings and strong, laced, black boots. Of course she didn’t run around with bare feet now she was fifteen, but those boots looked very hot and heavy.

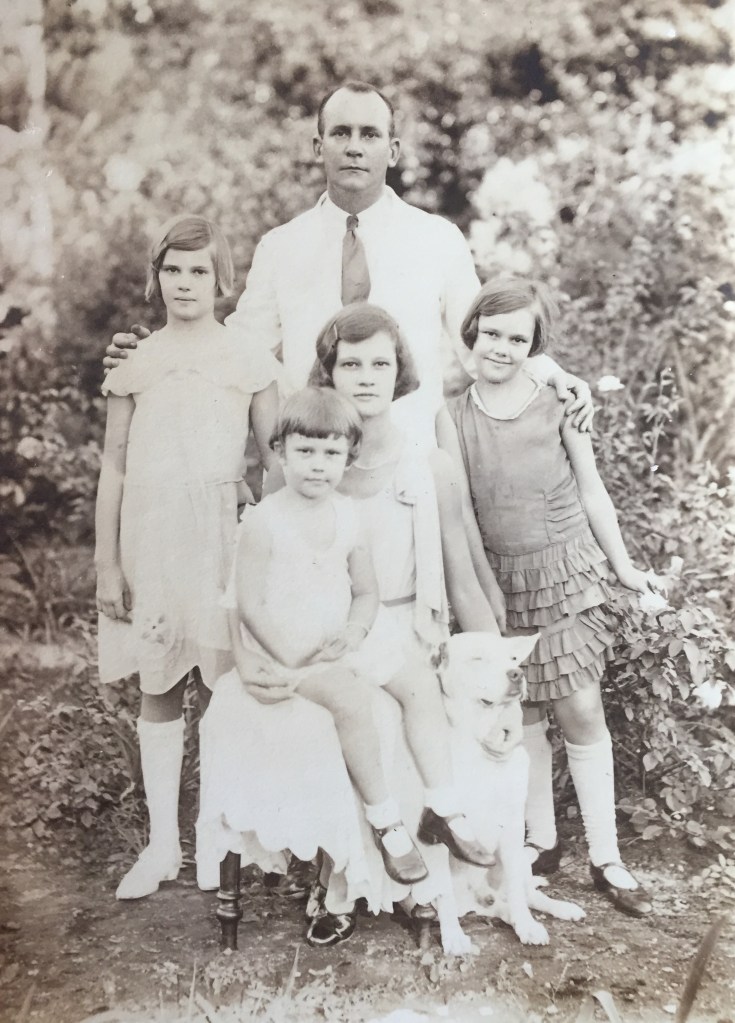

Suddenly her heart felt as hot and heavy as those boots. Nearly three years ago Fred had gone to school in England and she had known that it would be her turn next. She had been breathlessly excited at the thought of England: seeing the wonderful sights of London, the palace where the King and Queen lived, the beautiful countryside; and eating an apple, all the things Fred wrote about in his letters home. Now she could smell the frangipani and orange blossom from the garden and feel the cool overnight breeze. Some of the family were still on the verandah and she could hear Mother’s voice. She wouldn’t see Mother for years, nor her brothers and sisters at home. She would be eighteen years old when she saw them all again. The enormity of it flooded over her and for the first time she realized what she was facing. When she had first heard that Doris was only coming for the ocean voyage and to see London, because she was delicate, she had been quite pleased because Doris could be so bossy, but now! How she wished they could spend those three long lonely years together. Slowly Carol got ready for bed and her last night at home.

In the morning all was rush and bustle. Sending trunks and other luggage down to the dock; trying to choke down breakfast; saying goodbye to the servants; and last of all hugging Mother with tears streaming down her cheeks. She clambered into the carriage with Dad and Doris, and Dad said, “You two can go on board straight away and get settled in your cabin. I want to talk to the Captain and make sure all the cargo is well stowed”. He kindly gave them each a little pat as Doris snuffled and Carol dried her eyes.

“How will we know which is our cabin?” Doris asked.

“Oh, someone will show you,” Dad said, and as the carriage stopped he jumped down and headed for the small boat waiting for them. He helped the girls in and then marched away. The boatman began slowly rowing them out to the steamer anchored off shore in deep water. It was an English steamship line which Father dealt with in his business to take sugar, cotton, arrowroot, and other island products to England, and to brings back all the goods which Hazell & Sons sold in their big store on the harbour.

Seen from Windsor on the hill above the town the ship had looked quite small, but as they came closer it seemed immense as the huge side towered above them.

“How will we ever get up there?” she whispered to Doris, thinking of the boys’ pirate stories and climbing up rope ladders or ropes. She was relieved to see a reasonable wooden ladder tethered to the ship’s side and a kind middle-aged officer coming to help them up. He showed them down to their cabin and explained that Dad was in the next one and that there were seven other passengers. The girls looked around the tiny neat cabin with two little bunks, one above the other. There was a cupboard and a small washstand with the basin sunk into the top and a chest of drawers with a mirror on the wall above. The porthole was open and peering out they could see the ocean with Bequia in the distance.

“We won’t have much room for clothes in here,” said Doris. “But your stuff is marked Not Wanted On Voyage anyway.”

“Let me have the top bunk, Doris” begged Carol.

“With pleasure, my dear. I don’t fancy being tossed to the floor if we have a storm.”

“We won’t have a storm,” said Carol firmly. “Fred said that it was as smooth as going out fishing at Villa all the way over.”

Carol was regretting the heavy skirt and solid boots, and wished she had on a light cotton dress like Doris, but she had wanted to be an English schoolgirl at once. She decided that when their bags did arrive, she would change.

“Let’s go upstairs,” she said. ” We can see if Dad is on board yet.”

Up on deck they found Dad talking to one of the officers. There was much activity as the ship prepared to leave. The engines were rumbling, the ladder was stowed away, and slowly the ship began to turn while the sirens and whistles blew. On the dock they could see Willie and Muriel and Trixie waving, and up on the verandah at Windsor stood Mother, a little figure waving a white handkerchief. Before long the people, then the houses and mountains grew smaller and smaller until St. Vincent itself was just a speck on the horizon.

The girls enjoyed the voyage, and as Carol had predicted, there was no storm, although the sea became more boisterous as they entered the English Channel. The sky was clouded and their first sight of England was through a grey morning mist. As they sailed on, the sun came out and they caught glimpses of green fields and trees with villages and houses and finally Dad pointed out a line of whitish grey along the shore and said, “Look- those are the white cliffs of Dover.”

By afternoon they were sailing up the Thames to Tilbury Docks and the sun had disappeared behind sullen clouds. The girls stared at the huge busy river with its crowds of boats, tugs, ships, and barges. Looking at the great dirty river and the dark, grimy warehouses and buildings along each shore, the girls could hardly believe that this was London.

With many attendant tugs and loud hoots and whistles they were at last firmly fastened to the dock and the ship’s engines were still. All the passengers had been ready for hours and looking down, Carol could see there were friends and relatives waiting below.

“Where’s Fred?” she asked Dad.

He grunted. “Fred is still in school- we’ll see him in a few days. Now I’m going to take you girls onto the dock. Our luggage should be there very soon, and you can stay with it until I see to Customs and the rest of the paperwork.”

By this time there was a thin drizzle falling and it was beginning to get dark. The girls sat quietly on the trunks in the shelter and waited- neither of them had much to say. Dad seemed to be a very long time and they were getting hungry and chilled when he came with a cab and hurried them off to the hotel.

At first the streets were narrow and cobbled, crowded with carts, barrows, and poorly dressed people. There were tiny, dirty houses on each side with women standing in the doorways and children huddled out of the rain. Gradually they came to wider, smoother streets and the horses were able to go faster, the street lamps were beginning to shine on the greasy pavement and the shops were brightly lit. The houses they passed were bigger but still tightly crowded together, with no trees or gardens to be seen anywhere. The girls just sat and looked out of the cab windows- houses, horses, people, lights, and noise- it was a terrifying new world. After along time they drove into quieter streets and pulled up at a small hotel. As they entered the pleasant, lit hallway, an imposing man came forward and greeted Dad warmly as a well remembered guest.

“I’m very pleased to welcome the young ladies,” he said. “Your rooms are ready and dinner is just being served in the dining room. Billy, show Mr. Hazell and his daughters to Rooms 16 and 17.”

Upstairs and along a corridor they followed the small bell boy and were shown into a large bedroom. Billy struck a match and lit a gas lamp on a bracket by the wall and the bright light showed them a big bed and heavy dark furniture with red plush curtains across the windows. Dad was in a room opposite and called to them, “Hurry up and wash, and then we will go down to dinner.”

Following Dad downstairs Carol thought, “I’m going out to dinner in a hotel with strange people. I’ll never be able to eat a bite.” But when they were seated at a comfortable table with white linen and shining silver, she discovered that all the people were far too busy eating to look at her, so she was able to enjoy the roast beef and Yorkshire pudding which Dad decided was the proper thing for their first dinner in England.

Later, they sleepily unpacked and washed in the hot water the maid had brought up in a shining copper jug.

Doris got into bed first and said, “Pull back the curtains, Monks, and see if the window is open. It’s sort of stuffy in here.”

Carol pushed the heavy curtains aside and said, “Yes, the window is open, but I think the smell is just London. How do I put out this light? I’ll have to climb on a chair to reach it. I never saw a gas light before.”

“Oh, just blow it out, the same as the lamp at home,” said Doris, who had never seen a gas lamp either.

The girls slept soundly, so soundly that the chambermaid’s knock did not waken them and Dad finally marched in at 8:30 a.m. to see why they weren’t ready for breakfast.

The gas fumes were faint since the windows had been open, but the girls were hastily wakened up and roundly scolded by Dad, the chambermaid and later, the Manager. “Don’t you girls know anything?” said Dad.