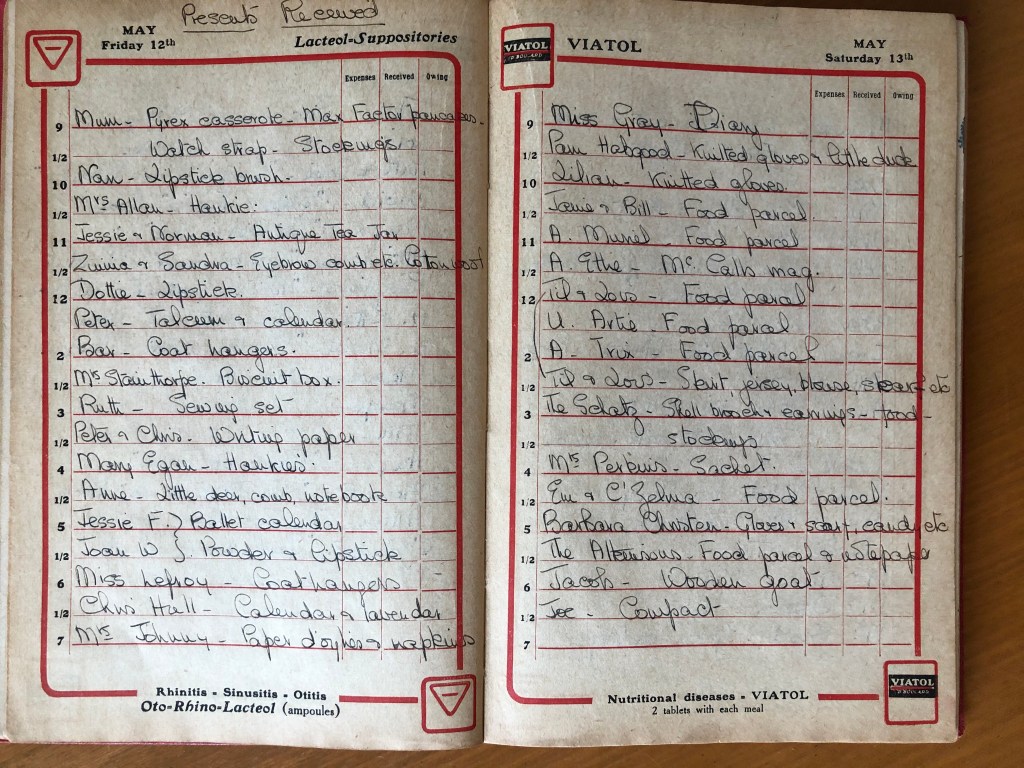

My mother introduced me, at the age of fifteen, bored and disgruntled at our rented summer cottage with nothing new to read, to Georgette Heyer, then coming out in paperback. I fell in love with her books, read my mother’s copies, and joined my friend Janet in collecting all we could. The fact that Cynthia had had a ball in her honour when she was 21 put her firmly in the Georgette Heyer class in my mind. One of the exotic stories I remembered from childhood was Cynthia’s coming of age ball. She had been the focus of family and friends on Her Day – the closest we would ever come was the high school graduation dance in a hotel when we were 18, where we would as always be in competition with the popular and more sophisticated ‘in’ girls. She may not have had A Season or been Presented as they had in the Regency- I didn’t know or care about 20th century debutantes- but she had gone to dances and had one of her own. However, Cynthia’s vague allusions to her 21st birthday suggested it had not been a night of complete pleasure.

I remember as an adult asking questions to try to get a handle on the class she lived in- was it common in her circle to have a Coming-of-Age ball? Did Jessie Muir, a doctor’s daughter as well, but one whose job after completing school was to manage her widowed father’s house, surgery, and phone, have a ball? Did Dottie, who shared my mother’s domestic science training and also became a teacher, have a ball? Did boys have an equivalent celebration? I got no clear answer. It could be that Gordon wanted to indulge his daughter and she was not appreciative; that her feelings towards him were affected by the difference of opinion over her college training; or that events in the future coloured her opinion of her father as she looked back on what, at the time, she enjoyed. I have no idea how big this dance was, or whether it was a success. All I know is that what she remembered were the flaws in the evening, not the enjoyment.

(And, by contrast, what do I remember of my high school graduation dance? Well, not much. It was the end of the sixties- hippies and free love were cool, dating/pairing off/marrying was not, really, except that if you weren’t in a relationship, you knew you were tagging behind as always. But at my life stage and academic level, I was not ready for any of that- along with the rest of my high school class, all 5 of the Grade 13 classes, I was off to university with at least 3 years of that before we would consider settling down. The idea was to go away to university first year and snag a date for your high school graduation in October. I had no interest in that so I begged my cousin Bruce to be my escort and he very kindly obliged. We returned for the graduation weekend- Thanksgiving?- had the usual tedious ceremony in rented gowns, and with close friends, organized ourselves for the evening.

I remember my dress: floor length, A-line, sleeveless, made of a strange material in a bluey-green aqua pattern with sparkling pale silver threads sort of laminated on a spongey foam backing, made by my mother and never worn again that I remember. (The foam disintegrated in time, leaving a nasty mess among other carefully preserved garments of the era in cotton or silk.) In fact, I remember very little- we went downtown to a hotel, we were all dressed up, we had familiar or unfamiliar dates, and it was awkward. I can’t remember that we fundraised the way graduation classes in schools I taught in did, so did we pay for the whole thing ourselves? If so, it was the done thing to do so, because everyone was there. There were round tables and food, there was no drink since we were all under age and no surreptitious drinking around me anyway, there was a band, we must have danced and caught up on each other’s lives, but my main feeling was that I had moved on. I loved my new university life at Trent where I wore blue jeans all the time instead of the incessant pressure of dress-to-look-good of high school, I had new friends who liked me, and I didn’t need my high school acquaintances any more. Bruce and my friend Janet would always be a part of my life, but that was the last I saw of most of those people, and I have to say I didn’t miss them.

I felt sorry for those, Janet among them, who had stayed at home in Ottawa and went to Carleton to university- scurrying around those tunnels greeting known faces from high school and only gradually finding better friends in other places. Living in residence at Trent had acquainted me at once with all the girls on my corridor, and helped me to become good friends with people in my college that I liked. Classes were small so within weeks, I had acquaintances in all the other colleges and knew my professors well enough to talk to. My life expanded in every direction- but enough about me. Maybe my poor memory explains Cynthia’s vagueness- she didn’t remember much either.)

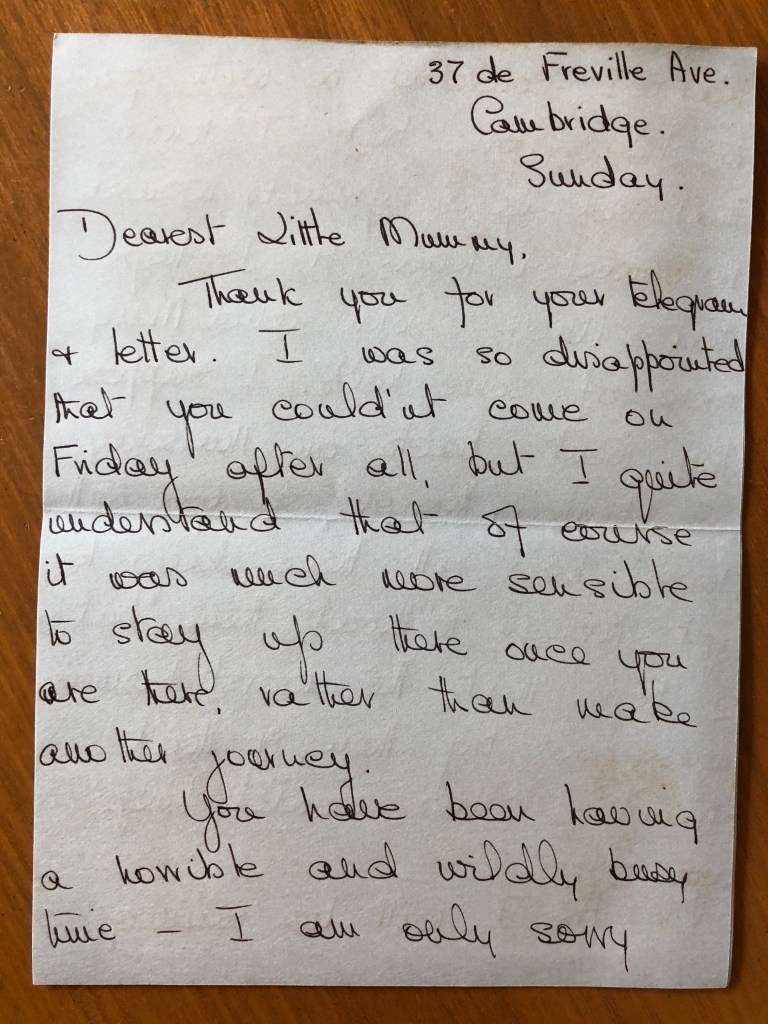

I don’t remember her description of her dress, but she did tell us about the cold water thrown on her appearance by her friend as Cyn appeared in all her glory. Meeting at her house was the party she would go to the dance with- her escort, and her close friend, as well as her parents. I don’t remember if it was Nancy, Jessie or Dottie, but the girl friend cried out as she twirled in front of them, “Oh Cynnie, you haven’t washed your neck!” (This entailed a pause in the story while little Canadians were given an explanation of coal fires and soot in 30s England, and an assurance that she had washed in a lavish bath and was totally mortified by this comment.) Even when it was discovered to be a shadow, not dirt, and the friend had apologized, and they had all moved on for a gay evening, it was the humiliation of the moment that Cyn remembered.

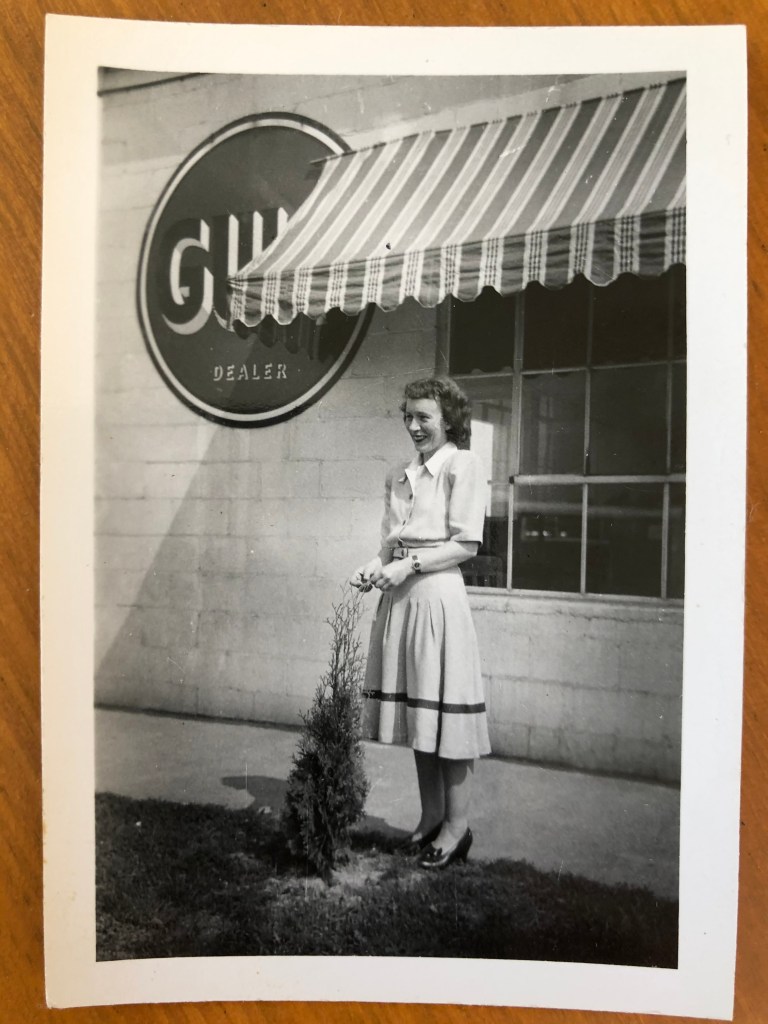

Was this the dance where the skirt of her dress was so tight that when she kicked a little too enthusiastically, she knocked herself right off her feet and landed on the floor? As her 1939 Travel Diary and her letters show, dancing was one of her favourite things.

I’m not sure if it was this night or a later event, but one of her friends was staying at the Ewings’ and going to a dance with Cyn. They went, they had fun, I assume they separated after since they had different escorts- and the friend got home before Gordon’s curfew while Cyn did not. That meant that Cyn was locked out huddling in the cold, the household was in bed, and the friend had to feel her way down in the dark through the unfamiliar house to let Cyn in. Another example of Gordon’s peculiar control.

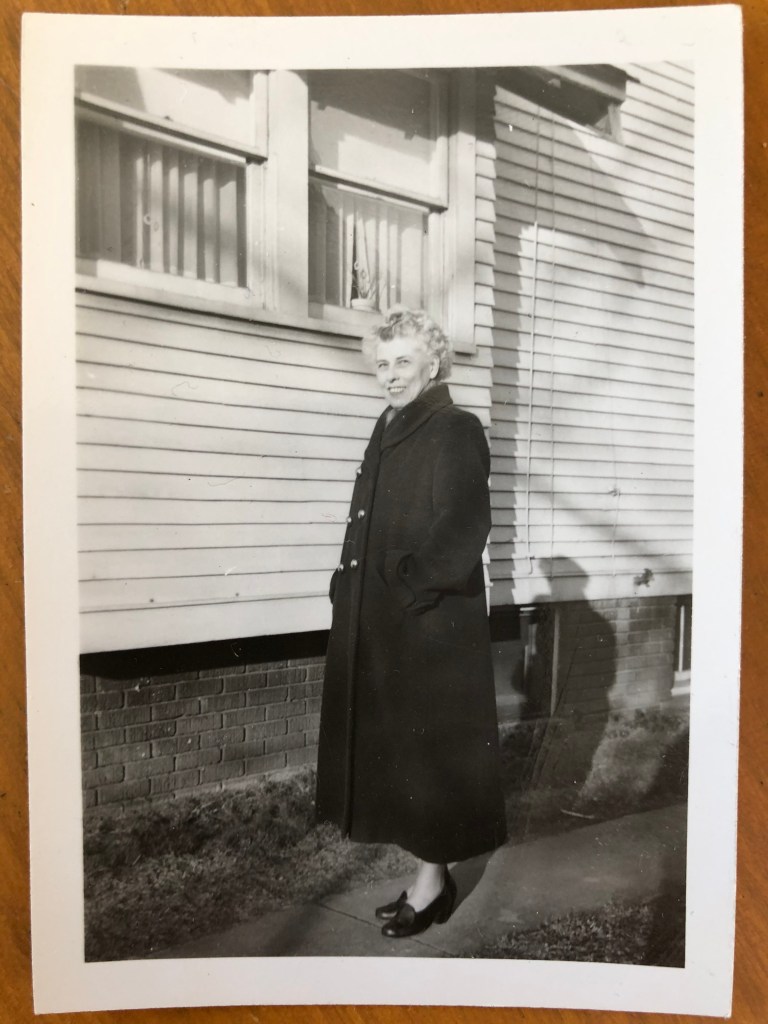

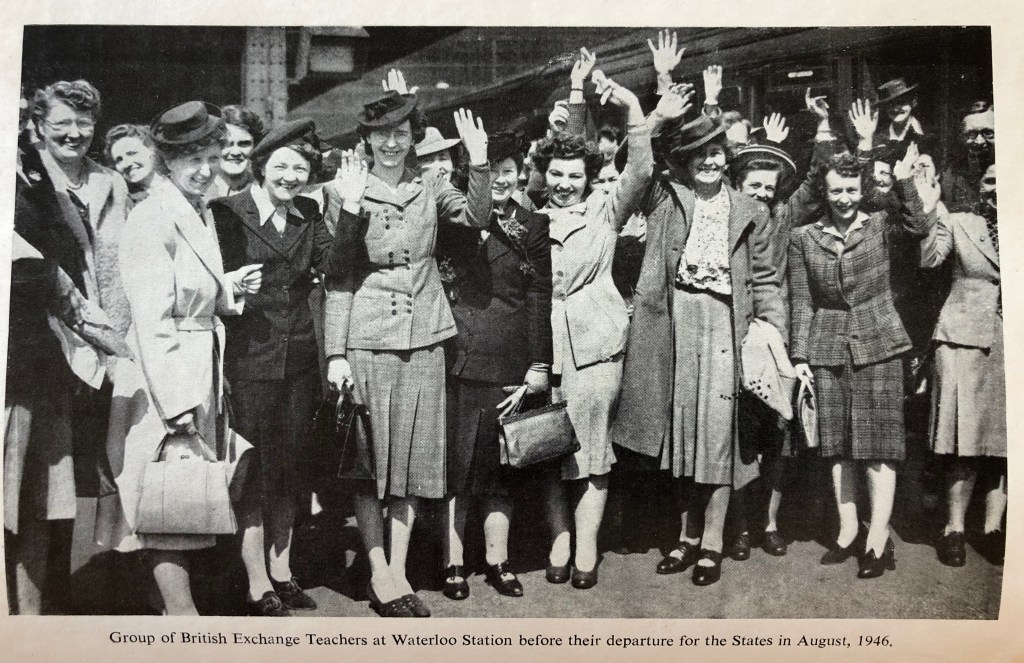

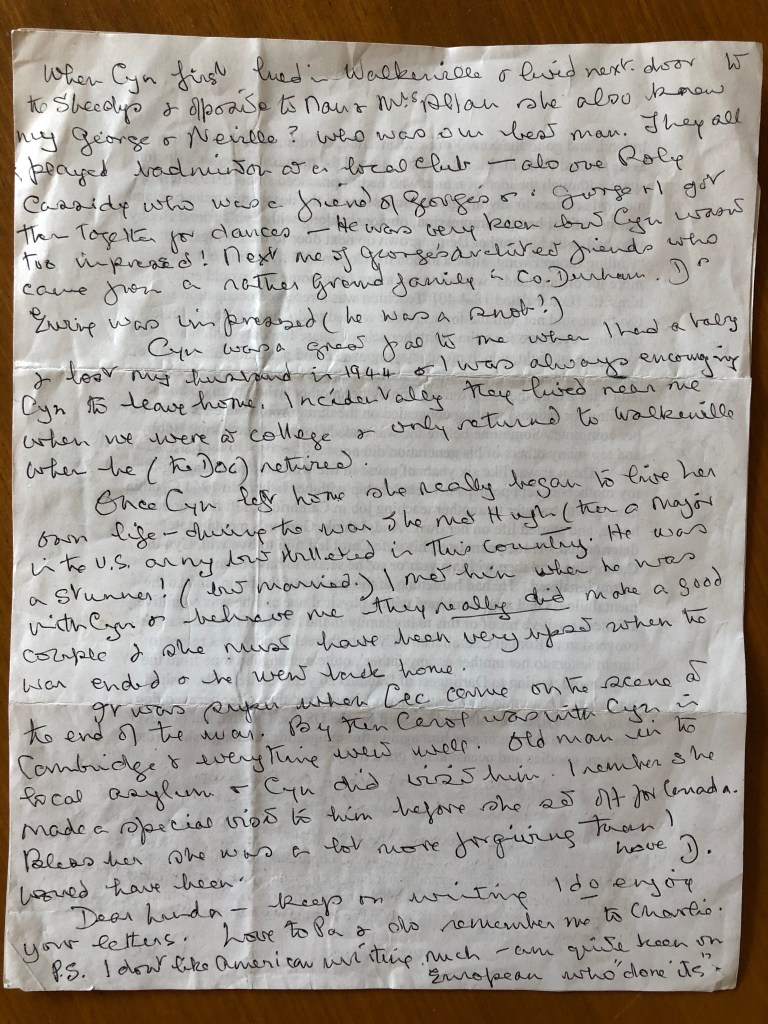

This underlines the difference between the position of women in the 30s and mine. My mother and I both were privileged. In my 20s, with teaching credentials and a teaching job, (having been given the gift of my education and the old car by my parents- much nicer than Gordon, I may add), I made enough in the 1970s to rent a one-bedroom apartment; run an old car to get me to my job, and drive away home or to friends in cities three to five hours away on weekends; go to visit my grandmother Carol in St. Vincent in March Break; and generally be independent. Cynthia, also a teacher, obviously did not. (I did have trouble finding a job for more than that one year- hence the adventure of CUSO in Nigeria 1978-80. Furthermore, I missed my university friends, finding myself out of step with the young couples at my school. But back to my mother.) Until the end of the war, through 8 years of teaching, she lived at home with her parents. And at least her father’s diktat had given her training, and her profession opened the way for her post-war exchange. Her friend Jessie had lived at home and acted as her father’s housekeeper and receptionist after her mother’s death- until he married again and did not need her any more. The solution? Early marriage.

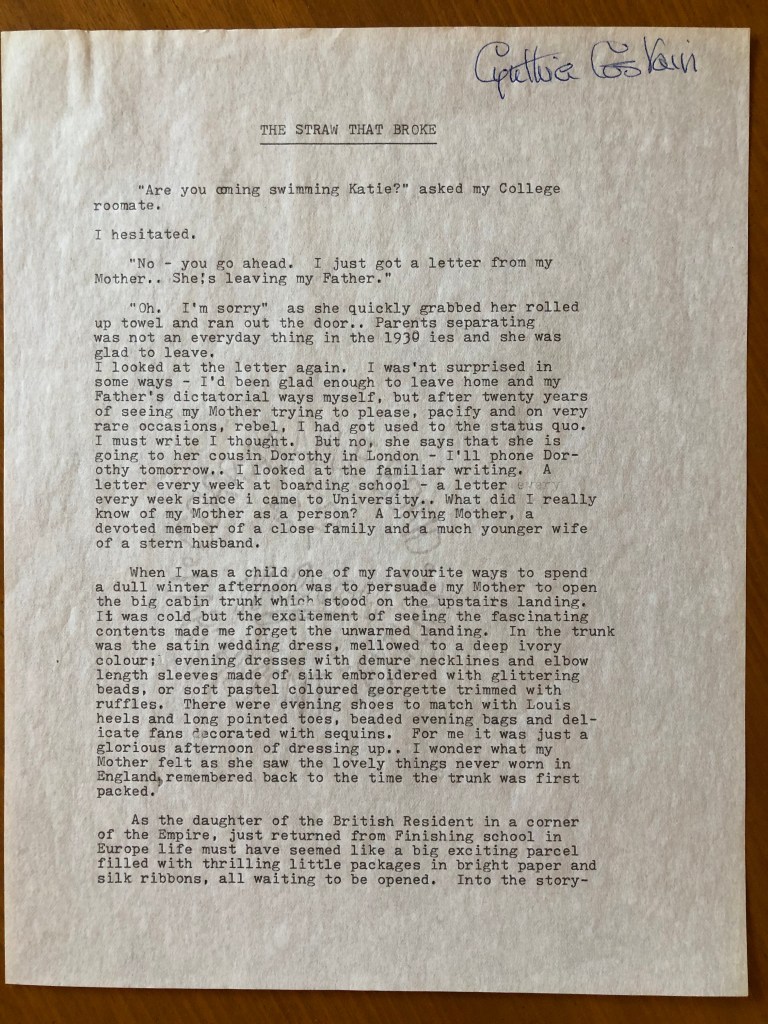

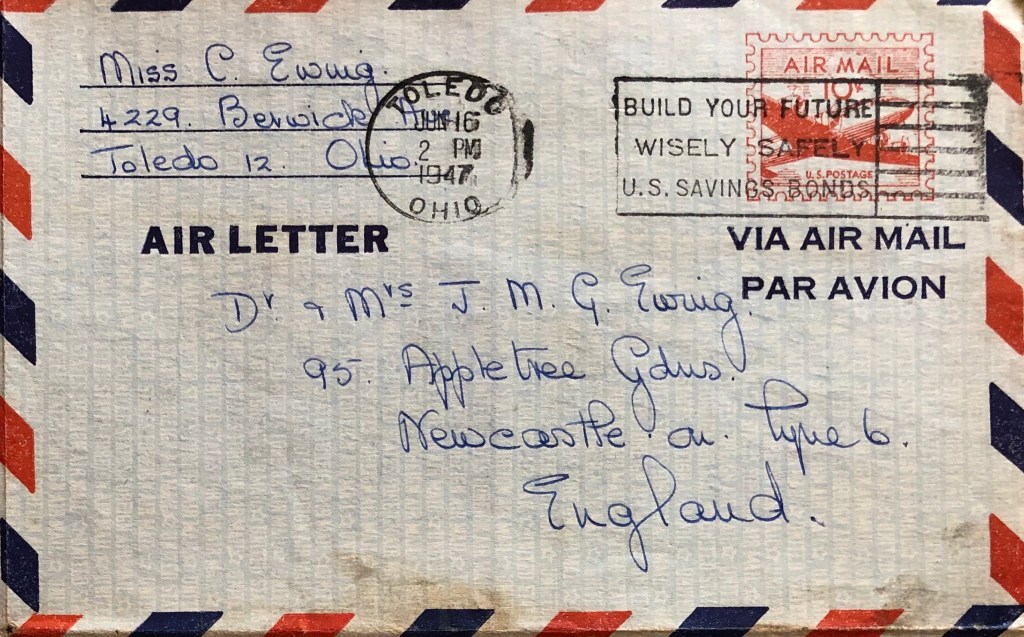

When she moved to Cambridge, Cynthia seemed to have a room in a house shared with women colleagues from her school, and did not rent a flat in a house until her mother joined her. Was it the salary or the culture? Unmarried women in the 1930s may not have needed chaperoning at this stage of the twentieth century, but they did not seem to live alone. My mother’s letters are full of older pairs of women sharing a life- lesbian couples or hard-up friends? The Great War had wiped out much of a generation of young men but working women were not paid equally- a thing we’re still coping with one hundred years later. And women teachers in the 20th century always have been held to a high standard of moral behaviour- along with the lower salaries. (My Canadian grandmother had more in common with my mother than either of them perhaps realized, coming from different generations in different countries.) But Cyn’s exchange year in America had given her experience of working in a different culture among people with different ideas- as my years teaching in Nigeria did me- which broadened her world view, as well as boosting her self-confidence. This maturity made her later immigration much easier than the experiences of many of the British war brides trying to cope with life in a strange new country.

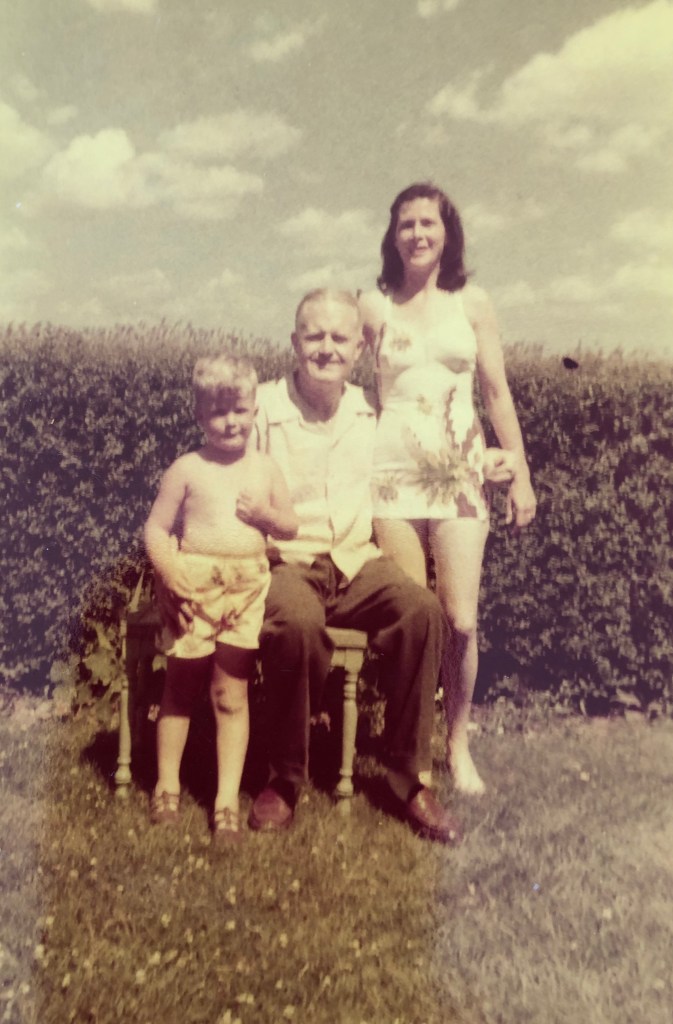

Cyn, at different stages of her life in different cities and countries, seems surrounded by friends and acquaintances in her own age group doing the exactly same thing as she- working, dancing and holidaying, then slogging through the war, all the time conscious that other people were suffering more than she, since saying goodbye to friends who did not return was not the same as death or widowhood.

But her post-war generation faced a different kind of Coming of Age. The Nuremberg Trials attempted to establish a universal agreement about the responsibilities of states and individuals, and the consequences of abuses. The world became more conscious of global connections, the UN established the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and in England, post war elections meant a Labour government moved to a better kind of attitude towards its citizens, instituting safety nets such as the National Health and changes in education and social services. Canada followed, with the 1949 baby bonus, for example, which was sent out in the mother’s name, and Cynthia would benefit. Again, she and her generation were all doing the same thing: getting married, getting pregnant, creating the world-wide Baby Boom- my generation- and, after she had emigrated, falling off on the letter-writing as she and her English friends produced offspring and got on with their lives far apart from each other, but still parallel.

It’s a pleasure to follow them into the post war era.